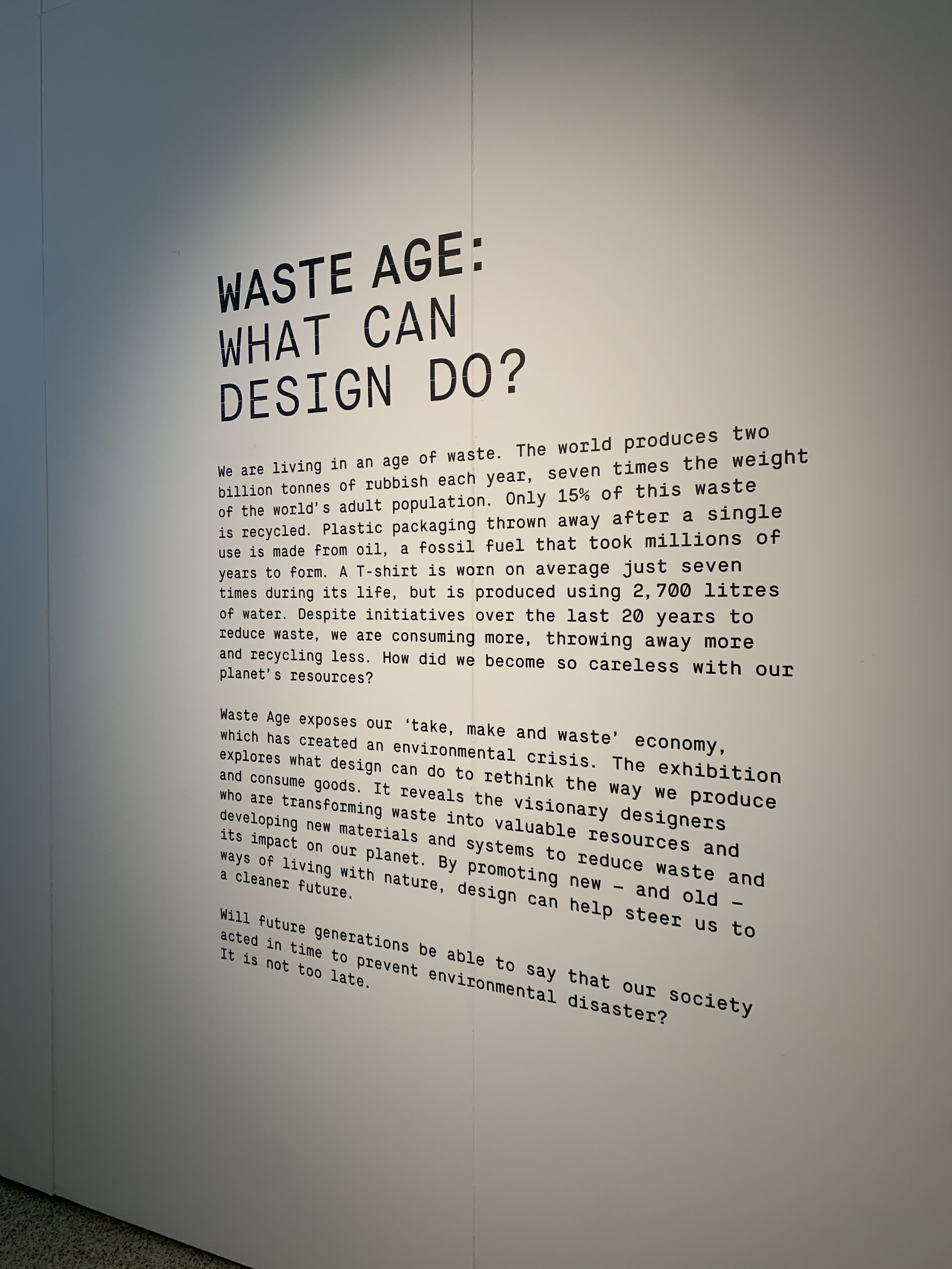

Waste Age & The Role of Design

As mentioned in last week’s post, I visited The Design Museum’s Waste Age exhibition in November. And, typical me, I’m only just writing it up now (in my defence, it’s been busy!). Anyway, it remains a deeply relevant topic and one that we must keep coming back to if we are to make any sort of change. So, I hope the delay can be forgiven…

The Issue

What is waste? It seems the definition is twofold:

A verb: "to use or expend carelessly, extravagantly, or to no purpose”. This clearly summarises our attitudes to consumption and our throwaway culture.

An adjective: “(of a material, substance, or by-product) eliminated or discarded as no longer useful or required after the completion of a process”. This is in line with Professor Rebecca Earley’s definition of waste as a design fault and designer Fernando Laposse’s view that waste represents a missed opportunity to optimise.

However we define it, there’s no denying that we are drowning in it. To be more specific, the world produces two billion tonnes of rubbish each year. To see that number in real time, visit The World Counts.

So why is it such an issue? Well, dumping waste, as well as other activities such as burning oil and gas to heat our homes and run our vehicles, contributes to climate change through the production of greenhouse gases. In short, these gases cause temperature rises which melt icecaps. In turn, melting icecaps cool the oceans and lead to rising sea levels, which can result in extreme weather events - ones that impact life on Earth. Yikes.

The Waste Age Exhibition exposed the problem and explored in depth what designers can do to rethink how we produce and consume goods.

The Evidence

Having established the statistics, the exhibition showed a number of examples that emphasised just how entangled waste and the natural world have become.

Cigarette butts are the most littered item on Earth with 4.5 trillion being discarded each year. Other commonly littered items include plastic bottles, lunch packaging, plastic bags, wet wipes, clothing and takeaway cups. The image above shows a chain made up of more than 6,600 bottle tops collected from Cornish beaches in one winter (between Dec 2015 and Feb 2016).

Plastic pebbles or ‘plastiglomerates’, as seen here, form when plastic waste melts (either in the sun or in bonfires), and combines with sand, shingle, seaweed and natural debris. The term was coined by Dr Patricia Corcoran and Kelly Jazvac.

The above two photographs, titled Oxford Tire Pile (1999) and Dandora Landfill (2016) form part of The Anthropocene Project, a collaboration by Nicholas de Pencier, Edward Burtynsky and Jennifer Baichwal. The project explores “the complex and indelible human signature on the Earth” (edwardburtynsky.com). Such images capture the often unseen industrial landscape.

Based in Ghana, artist Ibrahim Mahama explores the themes of globalisation, trade and colonialism. His commission for this exhibition exposes the dumping of European electronic waste in his country. Indeed, in 2009, Ghana was receiving 215,000 tonnes of e-waste every year, with much ending up in Agbogbloshie. In the absence of a formal recycling process, such waste is smashed or burned by local workers to get to the metals inside - a process that leads to injury, illness and toxic pollution. Since new electronic models are constantly being released, the process continues. The frames in the above image are made from materials within the process.

How Did We Get Here?

The exhibition moved on to question how we got here, with a lengthy timeline - a few dates stood out to me:

1700s - Waste was dumped from windows onto the street

1775 - First flushing toilet

1800s - Industrial Revolution gathered pace. Rural to urban migration exacerbated waste, especially with the dumping of synthetic products by factories

1862 - First (semi-synthetic) manufactured plastic

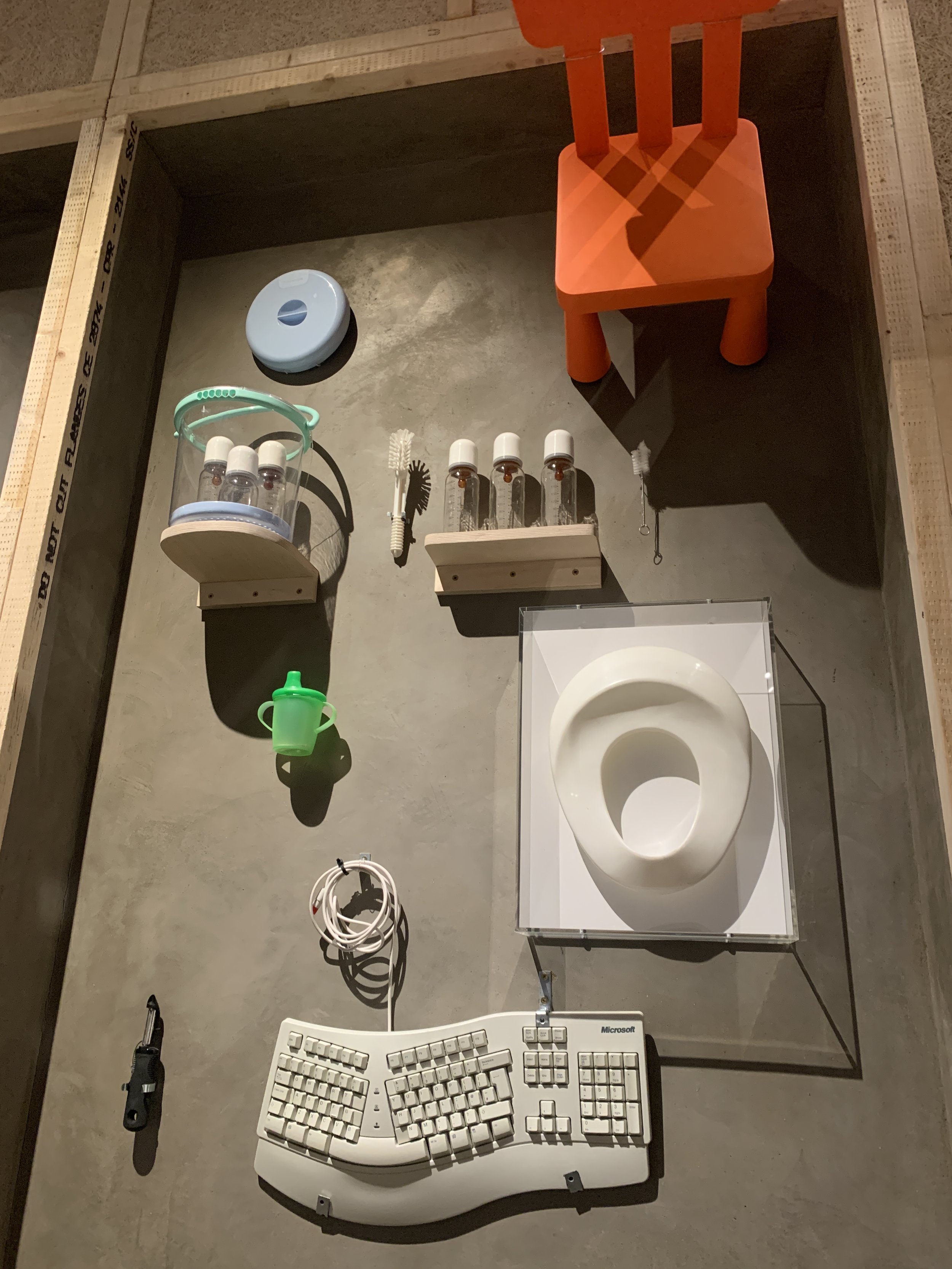

Side note - three reasons we love plastics so much…

They are easily cleaned/ sterilised

They have thermal properties, keeping us warm

They have diverse structural forms - from rigid to foam

1865 - Salvation Army founded in London. It started collecting, organising and recycling unwanted goods

1874 - First incinerators for waste disposal in UK

1875 - Public Health Act introduced. Households organised weekly waste in order for it to be collected

1911 - First plastic produced in lab, used for radios, cups and everyday objects (although the Science Museum notes this as being in 1906)

1933 - Polyethylene discovered (this went commercial in 1939)

1937 - First modern landfill opened in USA

1945 - Production of LPDE Sqezy bottle by Monsanto led to huge expansion in use of plastic packaging instead of glass

1949 - Tupperware made from polyethylene launched in USA. Lycra invented

1950s - Polyethylene bags first appeared. First polycarbonates produced.

Another side note - The glamour of throwing things away starting in the post-war period. Mass production and cheap materials reduced the cost of things, whilst time and labour became expensive, making repairs less effective. It therefore became more acceptable to throw away materials such as paper, glass, ceramics, plastics, tin, aluminium and textiles.

1970s - First Earth Day (which then became annual). Recycling logo designed by Gary Anderson

1971 - Victor Papanek wrote Design for the Real World, which argued that “design needs to move away from creating fetish objects for a wasteful society”. It is now one of the most widely read books on design

(I seem to have missed the 80s and 90s. Apologies!)

2000s - Global output of waste increased more in first decade of 2000s than in previous 40 years

2015 - UK 5p charge introduced for single use plastics

2016 - Paris Agreement, United Nations framework convention on climate change committed signatories to reduce carbon emissions

2019 - Greta Thunberg continued strike from school, demanding climate action from world leaders

2020 - Surge in plastic waste as a result of Covid, PPE and single use plastic packaging for health and hygiene concerns

What’s Next?

Having shown visitors evidence and explained how we got in this situation, the exhibition turned to how we move forward and change the narrative. What is clear is that we need more of a circular approach to design, manufacture and consumption - keeping minerals, metals and materials circulating in a supply chain, rather than burying or burning them. But, such recycling is undermined by lower-cost virgin materials and the idea that they are better in quality. We need design to add value and demand to recycled materials and to change the perception of how they look and how they can be used.

Naturally, I focused on construction, architecture and interior, photographing the examples that related to these areas.

The image above is a reclaimed stacking chair, made from 90% industrial waste.

Rotor Deconstruction is “a cooperative that organises the reuse of construction materials”. They “dismantle, process and trade salvaged building components”

The exhibition was certainly a wake up call. We have the opportunity to move beyond the Waste Age to a Conservation Age. However, we need to create consciousness in the public that translates into action. Unfortunately, the exhibition is no longer showing, but there are heaps of talks to go to, books to read, articles to take note of (like this one) to arm yourself with the knowledge and work towards a better future!